Fetal cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging may provide useful clinical information when echocardiography fails to adequately visualize the fetal heart, according to results of small, single-center study by researchers in Sweden.

In a cohort study that assessed 31 fetuses, CMR “had clinical utility, affecting patient management and/or parental counseling in 26 cases (84%),” wrote Daniel Salehi, MD, of Lund University, Skåne University Hospital, also in Lund, Sweden, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open. All cases were referred for CMR because echocardiography “could not visualize all relevant anatomy.”

Among the findings:

- Fetal CMR added diagnostically useful information to assess aortic arch anatomy in 16 of 20 cases.

- Fetal CMR visualized intracardiac anatomy and ventricular function in 13 of 15 cases involving assessment “of univentricular versus biventricular outcome in borderline left ventricle, unbalanced atrioventricular septal defect, and pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum.”

- In 3 of 4 cases of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, the use of fetal CRM helped delivery planning.

Additionally, CRM “provided valuable information for parental counseling in 21 cases (68%),” they wrote.

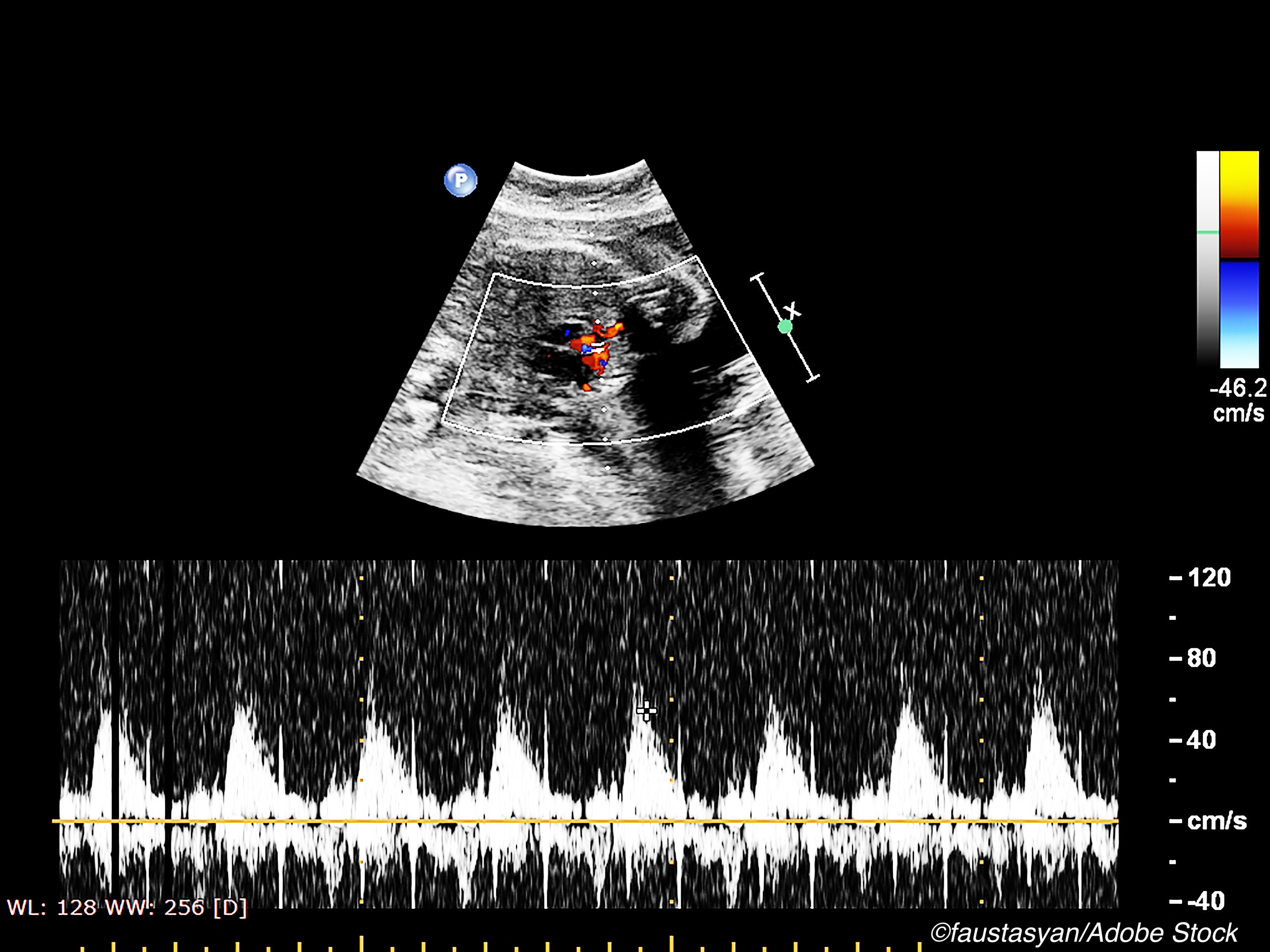

Since its introduction in 1980, fetal echocardiography—first with 2-dimensional imaging and more recently with color Doppler enhancement and 3-and 4-dimensional imaging—greatly advanced the field of fetal cardiology and enabled identification of cardiac defects as early as 12 weeks, wrote Bhawna Arya, MD of Seattle Children’s Hospital and the University of Washington School of Medicine, in an invited commentary published with the study by Salehi et al.

“Nevertheless, fetal echocardiography can be technically limited by factors such as maternal body habitus, oligohydramnios, uterine masses, gestational age, multiple gestation, and fetal position, which result in incomplete imaging of the fetal cardiac structures. In these cases, fetal CMR may prove to be an important adjunct to a fetal echocardiogram because it is not limited by these factors. Fetal CMR can image the fetal heart from any plane, allowing for a large field of view. There are no reported risks of fetal CMR to the pregnant mother or fetus,” Arya wrote.

There is a downside to fetal CMR: it costs significantly more than echo and takes significantly more time. Additionally, visualizing a very small, rapidly beating heart in a constantly moving fetus has significant technical challenges.

Yet, Salehi and colleagues wrote that their findings make a compelling case for CMR as a clinically useful supplement to fetal echocardiography. To illustrate their point, they called out one of the cases in their study in which a woman’s obesity “hampered diagnosis by echocardiography in a pregnancy with multiple risk factors for CHD because the fetal heart was not visible at all. In this case, fetal CMR demonstrated normal-sized left and right ventricles with normal systolic function, no inflow anomalies, no anomalies of outflow tracts, no anomalies of great vessels, at least 1 visible pulmonary vein to the left atrium, and no obvious direct or indirect signs of aberrant pulmonary veins. These findings allowed for delivery at the hospital closest to the patient’s home with nonurgent postnatal evaluation.”

Nonetheless, fetal CMR is not always accurate: In two cases, the information from CMR “did not agree with postnatal diagnosis and/or clinical course.” In one case “biventricular outcome was not possible due to a structural anomaly of the left atrioventricular valve that was unknown before birth. Likely, CMR could not visualize this due to limited resolution of current fetal CMR sequences, indicating a need for further improvement of spatial resolution. In another case, fetal CMR was incorrect regarding whether aortic coarctation would develop. Although commonly applied, neither atrioventricular annulus measurements nor ventricular morphology are certain factors for whether biventricular circulation will succeed postnatally nor is size or morphology of the aortic isthmus a certain biomarker for the development of postnatal coarctation.”

Moreover, unlike fetal echocardiography, which can be done early in pregnancy, the window of utility for CMR is late in gestation. Salehi and colleagues agreed with Arya, who cited this as a limitation of fetal CMR.

Finally, the commentary writer summed up the state of fetal cardiac imaging this way: “although fetal CMR provides an appealing opportunity for advanced, late gestation imaging, fetal echocardiography remains the gold standard for early and accurate in utero diagnosis and monitoring of CHD and other fetal cardiovascular diseases,” Arya wrote.

-

In a small, single-center cohort study, the use of fetal cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging provided useful clinical information in 84% of cases when echocardiography failed to adequately visualize the fetal heart.

-

Be aware that the cases included in this analysis were all referred following incoclusive fetal echocardiographs.

Peggy Peck, Editor-in-Chief, BreakingMED™

This study was supported by the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation Region Skåne, Skåne University Hospital, and Anna Lisa och Sven-Eric Lundgrens stiftelse för medicinsk forskning.

Salehi had no disclosures.

Arya had no disclosures.

Cat ID: 138

Topic ID: 85,138,730,914,41,138,925,481,96