Money doesn’t always talk when it comes to colon cancer screening. A systematic review and meta-analysis has shown that offering a financial incentive in addition to mailed outreach efforts to get more people to undergo colorectal cancer (CRC) screening had a negligible effect on an individual’s willingness to complete any type of screening, especially among populations who are disproportionately affected by CRC and who therefore need screening the most.

With mailed outreach efforts having a 30% estimated CRC screening completion rate, adding monetary incentives in the form of either cash or a chance to win a lottery or a raffle increased the screening completion rate to 33.5% (95% CI, 30.8-36.2%), Antonio Facciorusso, MBBS, Ospedali Riuniti di Foggia, Foggia, Italy, and colleagues reported in JAMA Network Open.

On meta-regression analysis, the magnitude of benefit from additional monetary incentives declined as the proportion of participants with either a low income or who came from certain racial and ethnic minority groups increased, the investigators added. “Financial incentives have been shown to promote healthy behavior such as smoking cessation, vaccination, and regular physical activity for a variety of conditions,” Facciorusso and colleagues wrote, though they noted that the association of financial incentives for improving cancer screening rates have so far been inconclusive.

Rachel Issaka, MD, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, and Jason Dominitz, MD, Veterans Health Administration, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington, pointed out in an accompanying commentary that financial incentives may motivate behavioral change when that change is simple, tied to controllable outcomes, and reinforces what an individual already wants to do. But they also concurred with the authors’ suggestion that people who are already primed to complete CRC screening may be motivated to do so when offered a financial incentive.

However, “[w]hen it comes to financial incentives, size matters,” Issaka and Dominitz observed. As they noted, small incentives such as those offered in the RCTs analyzed in the study can sometimes “backfire” by decreasing motivation and performance compared with no incentive at all.

“Rather than focusing on the intrinsic health benefits of screening, some individuals may interpret the offer of an incentive as compensation for exposure to adverse aspects of the test,” the editorialists wrote. “Thus, those who receive a financial incentive may defer future screenings without a monetary reward.”

They also suggested that offering a large financial incentive might be construed as coercive, especially with CRC screening, and possibly more so by those who are most unaware of the benefits of CRC screening and who remain underserved.

If financial incentives do not appear to motivate individuals to complete CRC screening, other interventions have been shown to increase CRC screening uptake.

These include mailed FIT outreach efforts along with patient navigation, which helps patients through the screening process including helping them make the decision to undergo CRC screening to begin with.

“The study by Facciorusso et al suggests that it is time we stop giving small financial incentives to individuals for questionable short-term benefits and to begin investing in practices that remove known patient, clinician, health system, and policy barriers to screening,” Issaka and Dominitz wrote.

“As the saying goes, ’money isn’t everything’ but in CRC screening, investing in evidence-based strategies could be everything for those who are affected by this all too common but highly preventable disease,” they concluded.

In their study, Facciorusso et al included a total of 8 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 110,644 participants in the meta-analysis. Approximately half of participants were offered various financial incentives while the other half served as controls and were offered no financial incentives.

All 8 studies were done in the United States and were published between January 2014 and December 2020 and used a variety of financial incentives, including fixed incentives (ranging from $5-$20, with one trial offering a $100 incentive)—usually conditional on completion of a screening test.

Some offered participants a chance to win larger amounts of money of between $50 and $100 by way of a lottery or a chance to enter a raffle with a $500 prize.

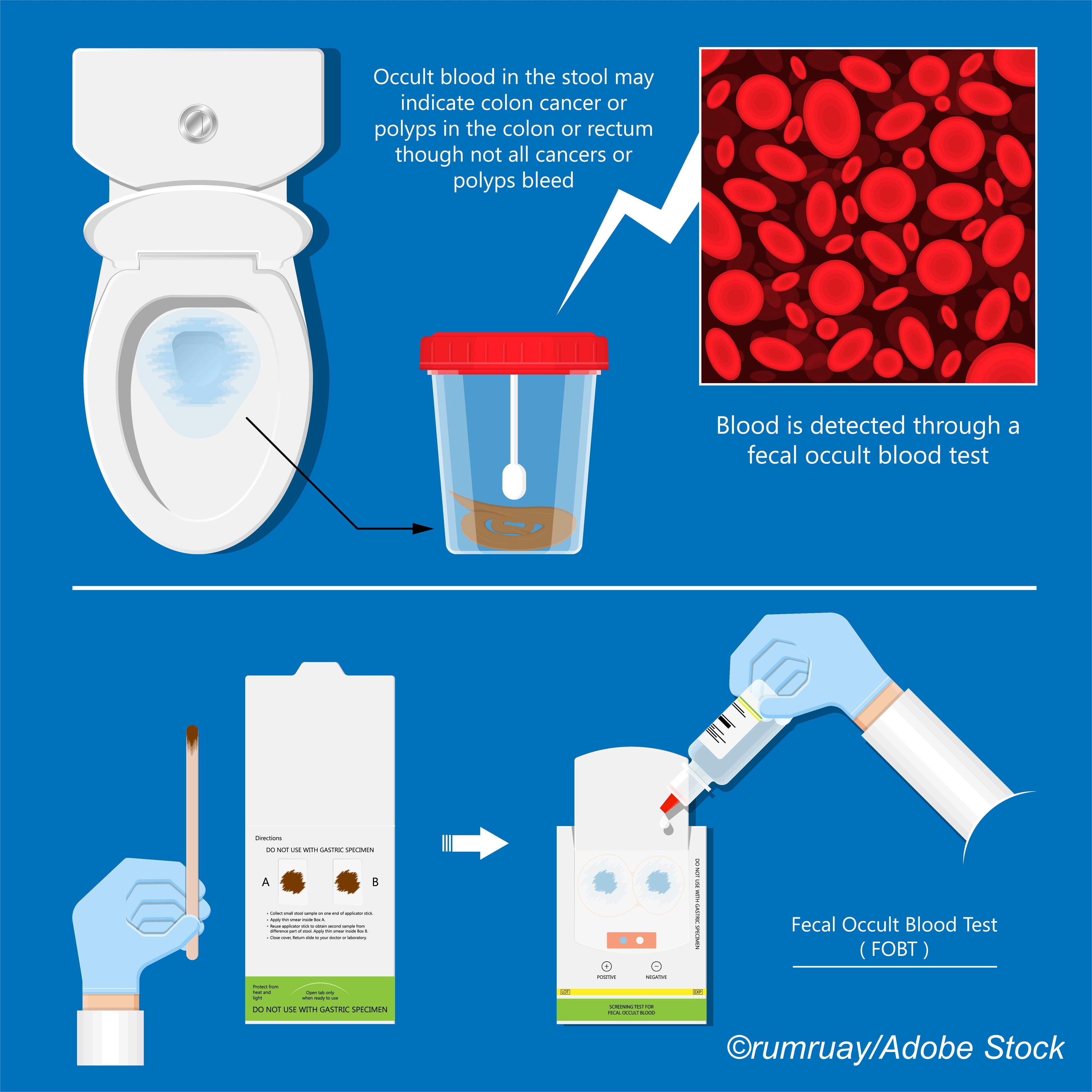

For all trials, the control group consisted of different degrees of outreach efforts such as sending individuals a fecal occult blood test (FOB) or a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) kit plus or minus reminders.

“Based on meta-analysis, adding financial incentives was associated with a 25% higher odds of CRC screening completion in the intervention group vs control group,” at an Odds Ratio (OR) of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.05-1.49), investigators noted.

However, overall, no significant differences were detected in the magnitude of benefit by either the type of financial incentive offered, the amount of incentive offered, the screening modality suggested, or the baseline outreach modality be it mailed outreach with a FOBT or a FIT kit, they added.

The authors cautioned that the evidence supporting the addition of financial incentives along with outreach efforts or reminders only was rated as low quality because there was considerable heterogeneity between the studies. Moreover, on sensitivity analysis which included only those trials in which participants were not up-to-date with CRC screening, “no clear benefit associated with adding financial incentives was observed,” the authors acknowledged.

On the other hand, financial incentives appeared to be more beneficial when screening completion was evaluated within 3 months of offering the incentive, suggesting that the incentive may simply have nudged those who were inclined to undergo screening anyway to get screened.

The authors suggested that for participants with higher incomes and with more favorable social determinants, financial incentives may tip the balance towards screening completion.

“On the other hand, underserved individuals may have such low awareness as well as face limited access and systemic barriers to health promotion that small incentive amounts may not be sufficient to overcome the systemic challenges,” they noted.

-

Offering financial incentives of any sort to mailed outreach efforts did little to promote completion of CRC screening, especially among those who need it the most.

-

Financial incentives may nudge individuals already inclined to undergo CRC screening anyway but for those who need it the most, financial incentives may be seen as coercive or as compensation for undergoing a distasteful test.

Pam Harrison, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health among others.

Facciorusso had no conflicts of interest to declare.

The editorialists had no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Cat ID: 23

Topic ID: 78,23,730,16,23,192,925