A imaging-based score for estimating five-year risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) in patients taking antithrombotic agents for secondary stroke prevention may be superior to other scores, an analysis of observational data suggested.

The newly proposed score, called MICON-ICH, was developed from meta-analysis of pooled patient-level data from the Microbleeds International Collaborative Network (MICON).

A separate score for ischemic stroke risk, MICON-ischemic stroke, was also proposed — prediction outcomes were five-year risks of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (including intracerebral, subdural, subarachnoid, and extradural hemorrhage) and ischemic stroke (excluding transient ischemic attack).

“The MICON risk scores, incorporating clinical variables and cerebral microbleeds, offer predictive value for the long-term risks of intracranial hemorrhage and ischemic stroke in patients prescribed antithrombotic therapy for secondary stroke prevention,” wrote David J. Werring, PhD, of University College London in England, and co-authors in Lancet Neurology.

“Risk scores including cerebral microbleeds offer increased discrimination over clinical variables alone for the prediction of antithrombotic-associated intracranial hemorrhage in a large, multicenter, international population,” they added. “Although external validation is needed, this finding provides new evidence of how neuroimaging biomarkers can contribute to clinical prediction models.”

All participants in the included studies had previous ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack, all were taking antithrombotic drugs, and all had baseline MRI with quantification of cerebral microbleeds. Participants were followed a median of two years for ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage.

Points were assigned for number of cerebral microbleeds (up to 9 points), previous intracranial hemorrhage (5 points), age (up to 4 points), previous ischemic stroke (1 point), and treatment with an antiplatelet or vitamin K antagonist antithrombotic (1 point). Those in an East Asian population study were assigned 2 points based on higher bleeding risk for that cohort.

The authors’ review of the literature on ICH predictor scores found the highest c index — a discriminative measure that estimates the probability that a patient who experienced an outcome of interest had a higher risk score than someone who did not experience the event — was associated with the HAS-BLED score (0.53).

Comparing the two proposed scores for ICH and ischemic stroke, Steven M. Greenberg, MD, PhD, of Harvard University, wrote in an accompanying editorial that “the optimism-adjusted c index for the final intracranial hemorrhage model was 0.73 (95% CI 0.69–0.77) and the calibration slope was 0.94 (0.81–1.06). The MICON-ICH risk score is substantially better than the discrimination offered by scales, such as HAS-BLED, that do not incorporate cerebral microbleeds.”

“Cerebral microbleed count was also included in a parallel MICON-ischemic stroke risk score, but with more modest discrimination (c index 0.63, 95% CI 0.62–0.65), which is not clearly superior to previous scales,” Greenberg noted.

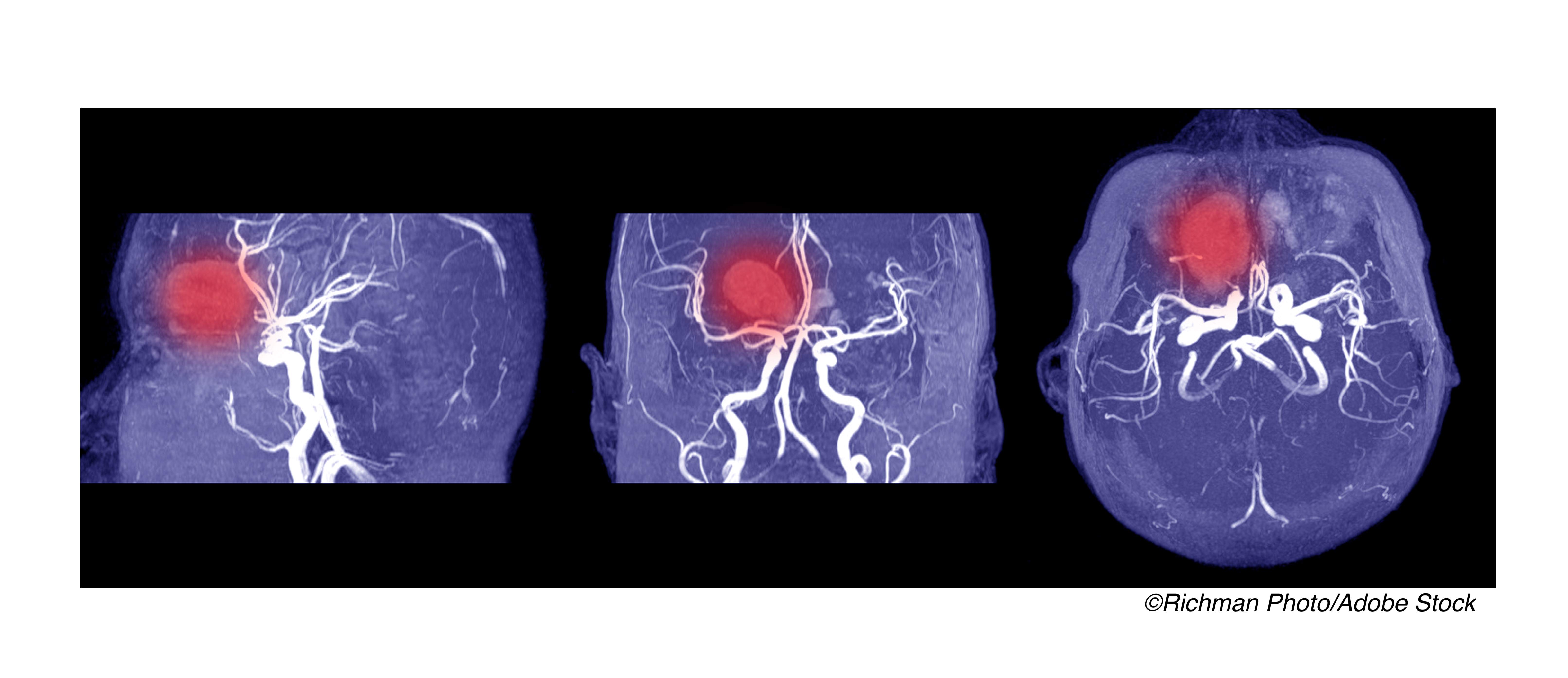

Most risk scores for ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage include only clinical variables, but MRI biomarkers are of increasing interest. MRI is increasingly available for most stroke patients and is noninvasive. Cerebral microbleeds are a MRI biomarker of vascular fragility associated with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke as well as dementia, aging, hypertensive microangiopathy, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Whether MRI findings of cerebral microbleeds can predict intracranial hemorrhage or ischemic stroke is unclear, though a 2019 pooled analysis drawing from the same data source (MICON) found that the adjusted hazard ratio for ICH increased more than that for ischemic stroke with increasing cerebral microbleed burden.

“The finding that cerebral microbleeds can predict intracranial hemorrhage indicates that intracranial hemorrhage tends to arise not from healthy small vessels, but from those with pre-existing hemorrhage-prone pathologies, such as hypertensive microangiopathy (also known as arteriolosclerosis) or cerebral amyloid angiopathy,” Greenberg observed.

Patients for the present study were recruited from August 2001 to February 2018. Overall median follow-up was two years for 15,784 participants. Mean age was about 71 and 57.6% of the cohort was male. Treatments included antiplatelet only (55.3%), warfarin or vitamin K antagonist (30.2%), direct oral anticoagulant (14.5%), and antiplatelet plus anticoagulant (8.6%).

Prior ICH was noted in 1.3% overall and ischemic stroke prior to the index stroke or TIA was reported by about 16%. Presentation was stroke rather than TIA for 81%. Overall, 184 intracranial hemorrhages and 1048 ischemic strokes were reported.

Most participants had no cerebral microbleeds (74%); next most common were one (11.2%) and two to four (9.3%), with 20 or more seen in 1.1% overall.

“There was good agreement between predicted and observed risk for both models,” the researchers noted. Predicted and observed risks for 5-year symptomatic ICH were, for selected MICON-ICH scores: score 0-2 (0.7% predicted, 0.2% observed), score 3 (1.3% versus 1.5%), score 6 (2.8% versus 2.9%), score 10 (5.9% versus 6.6%), and score 11 or more (12.3% versus 8.8%).

“Our scores are intended for use in patients in whom antithrombotic treatment is planned after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack,” the researchers cautioned. “The scores are not applicable to patients in whom antithrombotic treatment is contraindicated or for patients taking antithrombotics for primary prevention.”

“A high predicted intracranial hemorrhage risk might lead to more aggressive treatment of modifiable bleeding risk factors (e.g., hypertension and alcohol intake), review of concurrent medication, and consideration of non-pharmacological stroke prevention strategies if applicable (e.g., left atrial appendage occlusion in patients with atrial fibrillation),” they continued. “Our scores might also have applications in the selection of patients at high intracranial hemorrhage risk for future clinical trials and mechanistic studies of intracranial hemorrhage.”

Limitations include few patients with very high cerebral microbleed counts, reducing risk estimate precision for those with very high-risk. Factors that might have affected risk including cortical superficial siderosis, alcohol use, and renal insufficiency also were not included.

-

A newly-proposed score called MICON-ICH for estimating risk of intracranial hemorrhage in patients taking antithrombotic agents for secondary stroke prevention may be superior to similar scores, a pooled analysis suggested.

-

The score is not applicable to patients in whom antithrombotic treatment is contraindicated or for patients taking antithrombotics for primary prevention.

Paul Smyth, MD, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation and Stroke Association.

Werring reported personal fees from Bayer, Alnylam, and Portola, outside the submitted work.

Greenberg reported personal fees from Bayer.

Cat ID: 130

Topic ID: 82,130,730,8,130,38,192,925