Memory resilience in people with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was related to neurodegeneration, APOE genotype, and concomitant pathology, a small longitudinal cohort study found.

In people who had primary progressive aphasia with Alzheimer’s disease (PPA-AD), episodic memory was preserved at initial testing and showed no decline at a mean 2.35 years later, even though significant language function decline was seen, reported M. Marsel Mesulam, MD, of Northwestern University, and co-authors in Neurology.

In contrast, people with amnestic dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (DAT-AD) showed declines in both memory and language in evaluations that were a mean 1.7 years apart.

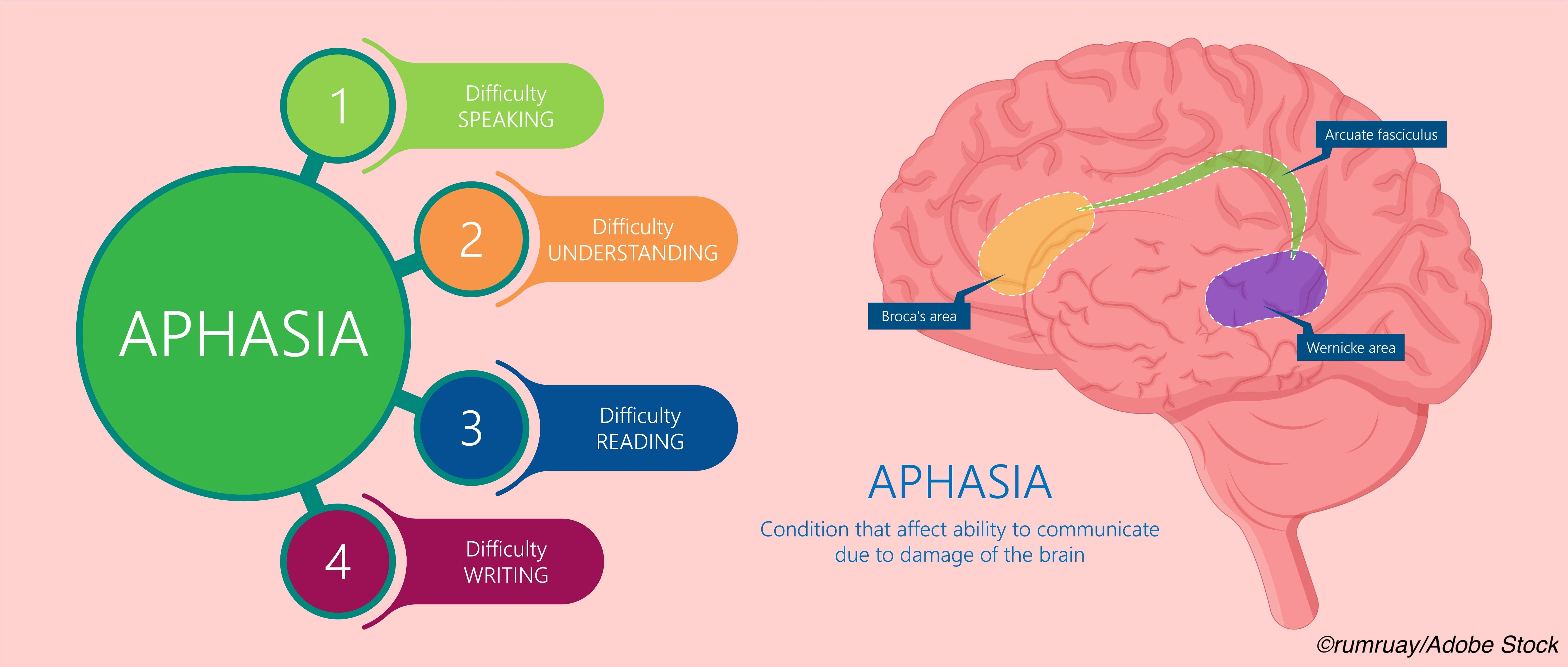

Primary progressive aphasia refers to several syndromes of impaired language that may include different pathologies. Variants include logopenic PPA, which is mostly associated with Alzheimer’s pathology, and semantic and agrammatical PPA, which are mostly associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration pathology.

“PPA is diagnosed when language impairment emerges on a background of preserved memory and behavior,” Mesulam and colleagues wrote. “Memory preservation in PPA is not just an incidental finding at onset but a core feature that persists for years despite the hippocampo-entorhinal AD neuropathology that is as severe as that of DAT-AD.”

“Asymmetry of mediotemporal atrophy and a lesser impact of apolipoprotein e4 and of TDP-43 on the integrity of memory circuitry may constitute some of the factors underlying this resilience,” they added. TDP-43 is a ubiquitous protein whose phosphorylated and truncated forms are a common pathologic finding in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, as well as about half of Alzheimer’s cases.

Mesulam and colleagues compared memory and language performance, genotype, imaging, and pathology for 14 patients with DAT-AD to 17 PPA-AD patients. All patients in both groups fulfilled the A3B3C3 criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, with severe neurofibrillary pathology in neocortex and the hippocampo-entorhinal areas.

Imaging showed asymmetric left-sided mediotemporal atrophy in PPA-AD, but autopsy revealed bilateral hippocampo-entorhinal neurofibrillary degeneration at Braak stages V and VI. Compared with DAT-AD, the PPA-AD group had lower incidence of APOE4 and of mediotemporal TDP-43 pathology.

Preservation of episodic memory in PPA-AD could be attributed to the unilaterality of mediotemporal degeneration, the authors noted, although “bilateral neurofibrillary degeneration at autopsy raises the need to look for additional factors that may mediate the preservation of memory in PPA-AD,” they said.

APOE4 may “magnify the selective vulnerability of the mediotemporal memory network to AD, perhaps by undermining compensatory neuroplasticity and neural efficiency,” they added. Reduced incidence of TDP-43 pathology may be another factor.

“Preservation of memory in the PPA-AD group is seen despite similarly widespread pathology in medial temporal lobe structures in both groups,” wrote Seyed Ahmad Sajjadi MD, PhD, of the University of California Irvine, and co-authors in an accompanying editorial. “It has been known for a while that presence of degenerative pathologies does not automatically imply the presence of dementia.”

“The effect of concomitant pathologies on cognitive impairment traditionally ascribed to AD pathology cannot be overlooked,” the editorialists added. TDP-43 pathology “is perhaps as important as AD pathology in development of cognitive impairment and dementia,” they said.

In the study, Mesulam’s group studied PPA-AD patients from the Northwestern University PPA Research program, which prospectively enrolls patients for longitudinal study. PPA participants had autopsy or biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s and two consecutive visits with language and memory assessment. The group of 17 patients included 10 males; participants had mean symptom onset about age 59 and initial testing a mean 6.3 years after symptoms onset. The group had 11 logopenic, five agrammatic, and one ambiguous variant of PPA.

The 14 DAT-AD patients were from the Northwestern Alzheimer’s disease center with diagnosis of typical Alzheimer’s dementia, and also had longitudinal memory and language data available. That cohort included eight males and mean symptom onset was about age 66, with initial testing a mean 4.3 years after symptom onset.

Mean age at death was 72 to 77 and was not significantly different between groups. Autopsy results were available for eight people in the PPA-AD group and all 14 members of the DAT-AD group. Pathology focused on neurofibrillary tangles and TDP-43.

Episodic memory was evaluated with different tests in the PPA-AD (the picture recognition subtest of the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test) and the DAT-AD groups (the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test). Language in both groups was tested with the Boston Naming Test; the PPA-AD group also had aphasia quotient scores from the revised Western Aphasia Battery.

“It seems reasonable to conclude that neurodegeneration, and not mere presence of pathology, is what correlates with clinical presentation in these patients,” the editorialists observed.

“This is an important notion in an era of development of targeted therapies that are increasingly aimed at those with no or minimal cognitive impairment,” they continued. “Distinguishing progressors from non-progressors among those with equal amounts of pathology is important, not only to avoid unnecessary exposure to side effects in non-progressors, but also to enable establishing the efficacy of these compounds in clinical trials.”

The results also suggest that “current controversies on memory in PPA-AD reflect inconsistencies in the diagnosis of logopenic PPA, the clinical variant most frequently associated with AD,” Mesulam and co-authors wrote.

Limitations include the relatively small sample size of the study. In addition, memory tests differed between groups.

-

Memory resilience in people with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was related to neurodegeneration, APOE genotype, and concomitant pathology, a small longitudinal cohort study found.

-

In people who had primary progressive aphasia with Alzheimer’s disease (PPA-AD), episodic memory was preserved at initial testing and showed no decline at a mean 2.35 years later.

Paul Smyth, MD, Contributing Writer, BreakingMED™

This project was supported in part by the National Institute of Deafness and Communication Disorders, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Davee Foundation, and the Jeanine Jones Fund.

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

The editorialists report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Cat ID: 33

Topic ID: 82,33,282,404,485,730,33,361,192,255,925

Create Post

Twitter/X Preview

Logout