As the Covid-19 pandemic drags onward, it might be time for public health leaders to focus their efforts on cutting airborne transmission by revamping indoor ventilation systems, experts argued.

In the time since the Covid-19 pandemic first began in early 2020, it has become clear that SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets that are inhaled at close range—while longer range airborne or surface transmission can occur, both are considered less risky than droplets that can be transmitted at ranges of 1-2 meters during everyday interactions, Julian W. Tang, PhD, of the University of Leicester in Leicester, U.K., and fellow authors explained in an editorial published in The BMJ.

“Wearing masks, keeping your distance, and reducing indoor occupancy all impede the usual routes of transmission, whether through direct contact with surfaces or droplets, or from inhaling aerosols,” they wrote. “One crucial difference, however, is the need for added emphasis on ventilation because the tiniest suspended particles can remain airborne for hours, and these constitute an important route of transmission.”

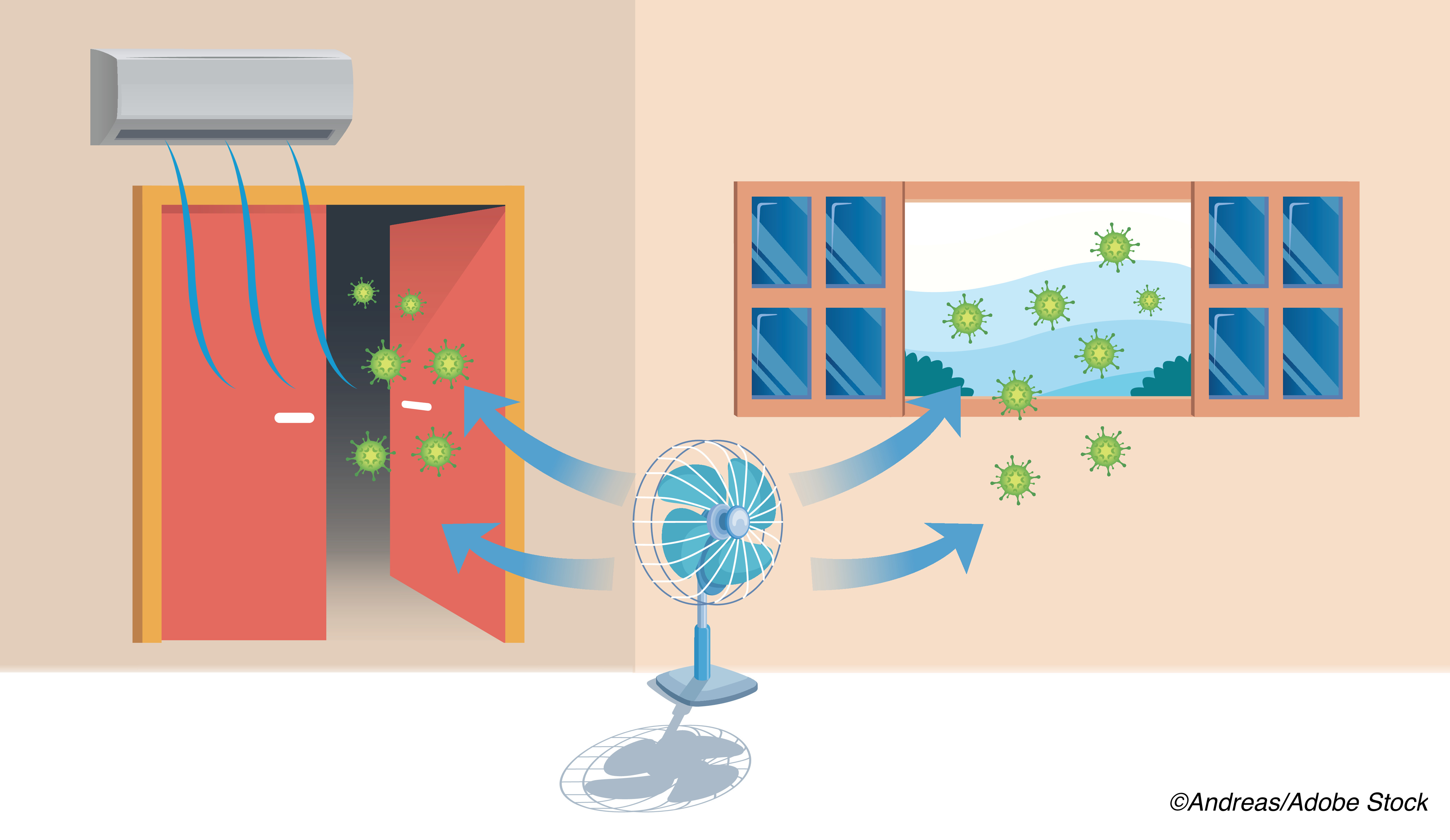

Tang and colleagues argued that, if someone in an indoor environment can inhale enough virus to cause infection when more than 2 m away from the original source, then air replacement or air cleaning mechanisms become crucial to reducing viral spread. “This means opening windows or installing or upgrading heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems, as outlined in a recent WHO document,” they noted. “People are much more likely to become infected in a room with windows that can’t be opened or lacking any ventilation system.”

And, they added, improved ventilation systems and air flow will have benefits beyond just reducing Covid-19—circulating air would likely also lead to lower rates of infection for other respiratory viruses, and perhaps even allergies and “sick building syndrome,” in which individuals experience acute health and comfort effects that appear to be linked to time spent in a building rather than a specific illness or cause, according to the EPA. As a result, workplaces would possibly see less absenteeism, leading to significant cost savings that could offset the expense of upgrading their ventilation system, the authors argued.

“Covid-19 may well become seasonal, and we will have to live with it as we do with influenza,” Tang and colleagues wrote. “So governments and health leaders should heed the science and focus their efforts on airborne transmission. Safer indoor environments are required, not only to protect unvaccinated people and those for whom vaccines fail, but also to deter vaccine resistant variants or novel airborne threats that may appear at any time.

“Improving indoor ventilation and air quality, particularly in healthcare, work, and educational environments, will help all of us to stay safe, now and in the future,” they concluded.

John McKenna, Associate Editor, BreakingMED™

Cat ID: 190

Topic ID: 79,190,730,933,190,926,192,927,151,928,925,934