Is psilocybin better or worse than traditional treatments for depression? It turns out the answer might be neither—results from a phase II trial showed no significant difference in antidepressant effects between psilocybin and escitalopram, researchers reported.

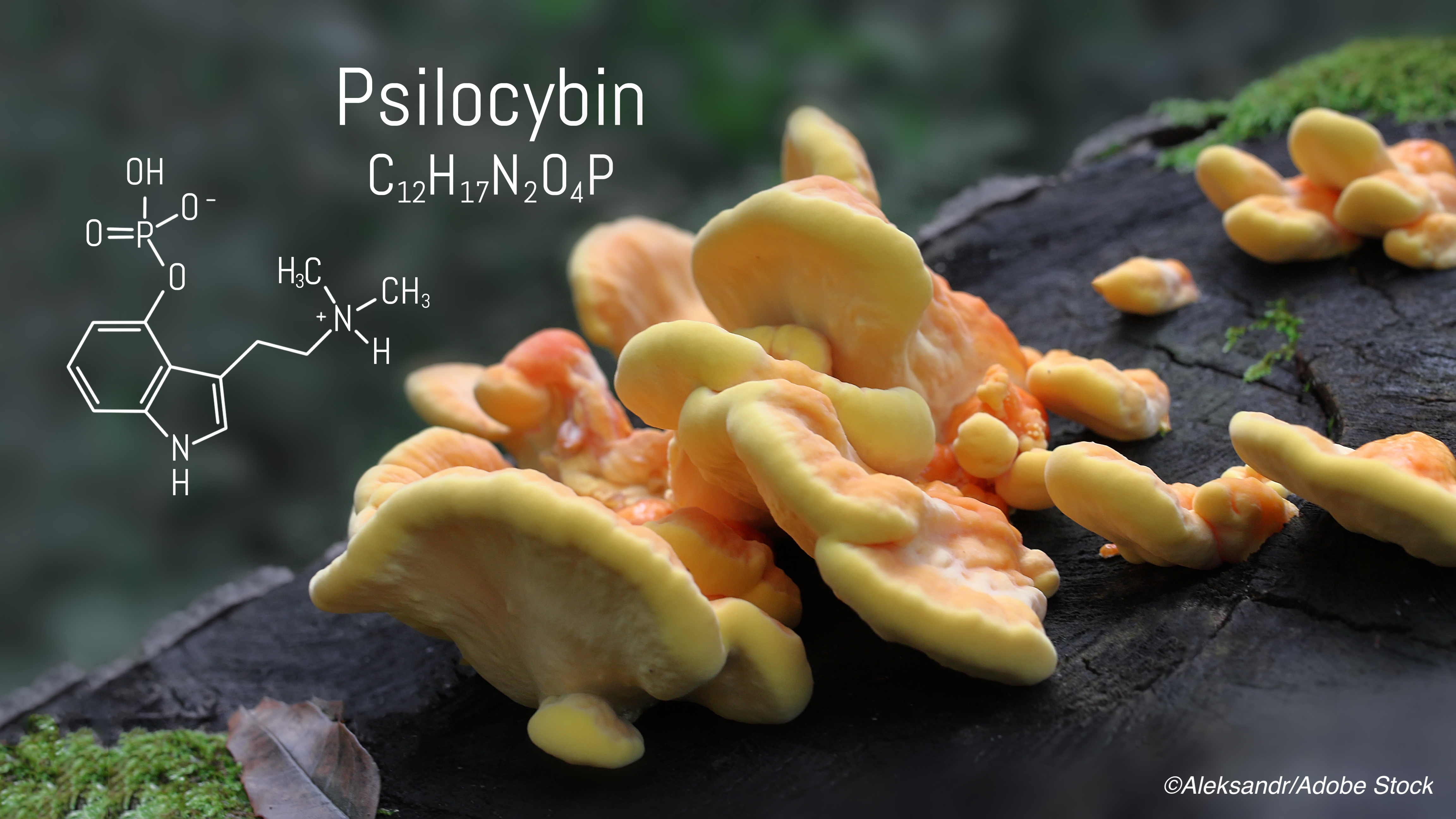

Psilocybin—the psychedelic compound found in so-called “magic mushrooms”—has previously shown promise as an add-on to therapy among patients with major depressive disorder, according to trial results published by Davis et al in JAMA Psychiatry. Around the same time, in November 2020, Oregon became the first U.S. state to legalize the use of psilocybin for mental health treatment.

In order to better understand how the therapeutic potential of psilocybin stacks up against more established antidepressants, Robin Carhart-Harris, PhD, of Imperial College London, and colleagues performed a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial pitting psilocybin against the selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor escitalopram in a cohort of patients with long-standing, moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder. Their results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“In this 6-week randomized trial comparing psilocybin with escitalopram in patients with long-standing, mild-to-severe depression, the change in depression scores on the [16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report] QIDS-SR-16 at week 6 (the primary outcome) did not differ significantly between the trial groups,” they wrote. “Secondary outcomes generally favored psilocybin over escitalopram; however, the confidence intervals for the between-group differences were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, and no conclusions can be drawn from these data. In both trial groups, the scores on the depression scales at week 6 were numerically lower than the baseline scores, but the absence of a placebo group in the trial limits conclusions about the effect of either agent alone.”

In an editorial accompanying the study, Jeffrey A. Lieberman, MD, of Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York, noted that while psychedelic drugs have shown encouraging results for depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders over the past decade—and the therapeutic effects were “tied to the subjective report of the user’s mystical experience”—the various trials had methodologic limitations, such as a lack of comparator treatments, short follow-up periods, imprecise dosing, and variability in treatment settings.

Lieberman wrote that, while the study by Carhart-Harris and colleagues is “an evidentiary milestone in the development of psychedelic drugs, it also reveals major knowledge gaps. It is unknown how these drugs produce their mind-altering effects. Psychedelics are partial agonists at the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2A (5-HT2A) receptor, but so are drugs such as lisuride that do not produce subjective effects.”

A fundamental question, he added, is whether “the putative therapeutic effects of psychedelics would require a patient to have a mystical experience or would occur in its absence through the pharmacologic effects on the serotonergic system or remodeling of neural circuitry.”

For their trial, Carhart-Harris and colleagues recruited patients ages 18-80 years old with long-standing, moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder. Exclusion criteria included immediate family or personal history of psychosis, significant health conditions that prevented trial participation, a history of serious suicide attempts, pregnancy, contraindications to selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), previous use of escitalopram, or “suspected or known presence of a preexisting psychiatric condition (e.g., borderline personality disorder) that could jeopardize rapport between the patient and their two mental health caregivers within the trial.” Patients discontinued any use of psychiatric medication at least two weeks prior to staring the trial medication, and psychotherapy was stopped at least three weeks prior.

In total, 59 patients were randomized 1:1 to receive two separate doses of 25 mg of psilocybin three weeks apart plus six weeks of daily placebo (n=30) or two separate doses of 1 mg of psilocybin three weeks apart plus six weeks of daily oral escitalopram (n=29). At the first visit, patients underwent MRI, completed cognitive and affective processing tasks, and attended a preparatory therapeutic session. At visit two, both groups received psilocybin. To standardize expectations, all patients were told they were receiving psilocybin, but the dosage was not disclosed—the psilocybin group received 25 mg, while the escitalopram group only received 1 mg, which is considered to have negligible activity.

The primary study outcome was change from baseline QIDS-SR-16 score at week six; the study also had 16 secondary outcomes, the most prominent of which were QIDS-SR-16 response (defined as a reduction in score of >50%) and QIDS-SR-16 remission (defined as a score of ≤5) at week six.

“The mean scores on the QIDS-SR-16 at baseline were 14.5 in the psilocybin group and 16.4 in the escitalopram group,” they found. “The mean (±SE) changes in the scores from baseline to week 6 were −8.0±1.0 points in the psilocybin group and −6.0±1.0 in the escitalopram group, for a between-group difference of 2.0 points (95% confidence interval [CI], −5.0 to 0.9) (P=0.17). A QIDS-SR-16 response occurred in 70% of the patients in the psilocybin group and in 48% of those in the escitalopram group, for a between-group difference of 22 percentage points (95% CI, −3 to 48); QIDS-SR-16 remission occurred in 57% and 28%, respectively, for a between-group difference of 28 percentage points (95% CI, 2 to 54). Other secondary outcomes generally favored psilocybin over escitalopram, but the analyses were not corrected for multiple comparisons.”

The incidence of adverse events was similar between groups, the study authors added, and no serious adverse events occurred. More patients in the escitalopram group than the psilocybin group experienced anxiety, dry mouth, sexual dysfunction, or reduced emotional responsiveness, and four patients in the escitalopram group discontinued treatment due to perceived adverse events. The most common adverse event in the psilocybin group was transient headache reported within 24 hours after the dosing day.

Study limitations included the brief duration of escitalopram treatment, as the drug has a delayed therapeutic action on depression; the study authors did not assess the effectiveness of blinding; and a lack of diversity among trial participants limits the study’s generalizability.

In his editorial, Lieberman concluded that the scientific community is still awaiting definitive proof of a therapeutic effect for psychedelics. And, he noted, if they do prove effective, informed consent and safety standards will need to be established. “How do we explain mystical, ineffable, and potentially transformative experiences to patients, particularly if they are in a vulnerable state of mind? What is their potential for addiction?” he asked.

“Given the controversial history, unique properties, and ambitious claims surrounding psychedelic drugs, their development must be guided by the most enlightened science and with the utmost methodologic rigor,” Lieberman added.

-

The results from a phase II trial found no significant difference in antidepressant effects between psilocybin and escitalopram.

-

While the study’s secondary outcomes generally favored psilocybin over escitalopram, the confidence intervals for the between-group differences were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, and no conclusions can be drawn from these data.

John McKenna, Associate Editor, BreakingMED™

Supported by a private donation from the Alexander Mosley Charitable Trust and by the founding partners of Imperial College London’s Centre for Psychedelic Research. Infrastructure support was provided by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Imperial Clinical Research Facility.

Carhart-Harris disclosed consultant agreements with COMPASS Pathways, Entheon Biomedical, Mydecine, Synthesis Institute, Tryp Therapeutics and Usona Institute.

Lieberman, who is a member of the editorial board of The New England Journal of Medicine, neither accepts nor receives any personal financial remuneration for consulting, speaking or research activities from any pharmaceutical, biotechnology, or medical device companies.

Cat ID: 55

Topic ID: 87,55,730,192,55,921,925